What is osteoporosis?

The word osteoporosis means spongy (porous) bone.

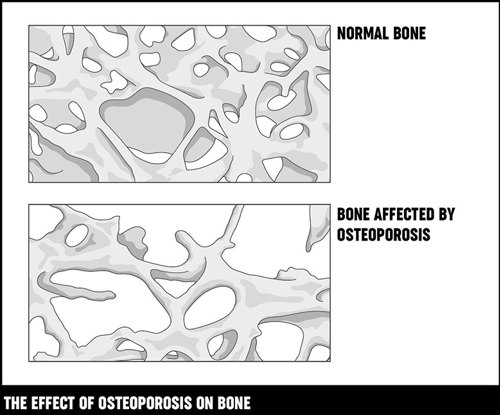

Bone is made up of minerals, mainly calcium salts, bound together by strong collagen fibres. Our bones have a thick, hard outer shell (called cortical or compact bone) which is easily seen on x-rays. Inside this, there’s a softer, spongy mesh of bone (trabecular bone) which has a honeycomb-like structure.

Bone is a living, active tissue that’s constantly renewing itself. Old bone tissue is broken down by cells called osteoclasts and is replaced by new bone material produced by cells called osteoblasts.

The balance between the breakdown of old bone and the formation of new bone changes at different stages of our lives.

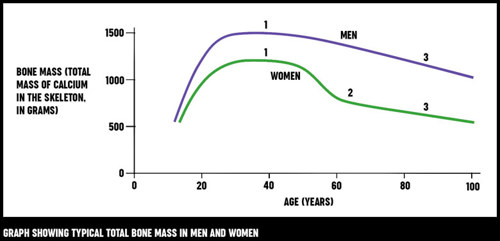

- In childhood and adolescence, new bone is formed very quickly. This allows our bones to grow bigger and stronger (denser). Bone density reaches its peak by our mid-to late-20s.

- After this, new bone is produced at about the same rate as older bone is broken down. This means that the adult skeleton is completely renewed over a period of 7–10 years.

- Eventually, from the age of about 40, bone starts to be broken down more quickly than it’s replaced, so our bones slowly begin to lose their density.

We all have some degree of bone loss as we get older, but the term osteoporosis is used only when the bones become quite fragile. When bone is affected by osteoporosis, the holes in the honeycomb structure become larger and the overall density is lower, which is why the bone is more likely to fracture.

Who gets osteoporosis?

Osteoporosis is common in the UK, and the risk increases with age. Anyone can get osteoporosis but women are about four times more likely than men to develop it. There are two main reasons for this:

- The process of bone loss speeds up for several years after the menopause, when the ovaries stop producing the female sex hormone oestrogen.

- Men generally reach a higher level of bone density before the process of bone loss begins. Bone loss still occurs in men but it has to be more severe before osteoporosis occurs.

A number of other risk factors can increase your chances of developing osteoporosis.

Symptoms

Osteoporosis often has no symptoms. The first sign that you may have it is when you break a bone in a relatively minor fall or accident (known as a low-impact fracture). Fractures are most likely in the hip, spine or wrist.

Some people have back problems if the bones of the spine (vertebrae) become weak and lose height. These are known as vertebral crush fractures. They usually happen around the mid or lower back and can occur without any injury. If several vertebrae are affected, your spine will start to curve and you may become shorter. Sometimes vertebral crush fractures can make breathing difficult simply because there’s less space under the ribs.

If you have a vertebral crush fracture you'll also have a greater risk of fracturing your hips or wrists.

Causes

Risk factors for developing osteoporosis include:

Steroids (especially if taken by mouth) – Steroids (corticosteroids) are used to treat a number of inflammatory conditions including rheumatoid arthritis. They can affect the production of bone by reducing the amount of calcium absorbed from the gut and increasing calcium loss through the kidneys. If you're likely to need steroids, such as prednisolone, for more than 3 months your doctor will probably suggest calcium and vitamin D tablets, and sometimes other medications, to help prevent osteoporosis.

Read more about steroid tablets.

Lack of oestrogen in the body – If you have an early menopause (before the age of 45) or a hysterectomy where one or both ovaries are removed, this increases your risk of developing osteoporosis. This is because they cause your body's oestrogen production to reduce dramatically, so the process of bone loss will speed up. Removal of the ovaries only (ovariectomy or oophorectomy) is quite rare but is also linked with an increased risk of osteoporosis.

Lack of weight-bearing exercise – Exercise encourages bone development, and lack of exercise means you'll be more at risk of losing calcium from the bones and so developing osteoporosis. Muscle and bone health are linked so it's also important to keep up your muscle strength, which will also reduce your risk of falling.

However, women who exercise so much that their periods stop are also at a higher risk because their oestrogen levels will be reduced.

Poor diet – If your diet doesn’t include enough calcium or vitamin D, or if you're very underweight, you'll be at greater risk of osteoporosis.

Heavy smoking – Tobacco is directly toxic to bones. In women it lowers the oestrogen level and may cause early menopause. In men, smoking lowers testosterone activity and this can also weaken the bones.

Heavy drinking – Drinking a lot of alcohol reduces the body’s ability to make bone. It also increases the risk of breaking a bone as a result of a fall.

Family history – Osteoporosis does run in families, probably because there are inherited factors that affect bone development. If a close relative has suffered a fracture linked to osteoporosis then your own risk of a fracture is likely to be greater than normal. We don’t yet know if a particular genetic defect causes osteoporosis, although we do know that people with a very rare genetic disorder called osteogenesis imperfecta are more likely to suffer fractures.

Other factors that may affect your risk include:

- ethnicity

- low body weight

- previous fractures

- medical conditions, such as coeliac disease (or sometimes treatments) that affect the absorption of food.

How will osteoporosis affect me?

There’s a great deal you can do at different stages in your life to help protect yourself against osteoporosis.

Exercise

Any exercise where the bones are made to carry the weight of the body, such as walking, can speed up the process of new bone growing.

The more weight-bearing exercise you do from a young age, the more this will reduce the risk of getting osteoporosis.

If you do have osteoporosis, doing weight-bearing exercise will minimise bone loss and strengthen muscles.

However, all forms of exercise will help to improve co-ordination and keep up muscle strength. This is important because muscles can also become weaker as we get older, and this is a risk factor for falling and therefore for fractures.

T'ai Chi can be very effective in reducing the risk of falls. Doing T’ai Chi regularly will strengthen muscles in the upper body, lower body and the core. It also improves balance.

Walking is a good exercise to improve bone strength and it is also good for keeping thigh and hip muscles strong, which is important to help people have good balance and prevent falls.

High-impact exercise such as skipping, aerobics, weight-training, running, jogging and tennis are thought to be useful for the prevention of osteoporosis. These exercises might not all be suitable if you have osteoporosis.

For more support, motivation and advice talk to your doctor, a physiotherapist or a personal trainer at a gym about your condition and the best exercise for you.

Diet and nutrition

Calcium

The best sources of calcium are:

- dairy products such as milk, cheese and yogurt (low-fat ones are best)

- calcium-enriched types of milk made from soya, rice or oats

- fish that are eaten with the bones, such as tinned sardines.

Other sources of calcium include:

- leafy green vegetables such as cabbage, kale, broccoli, watercress

- beans and chick peas

- some nuts, seeds and dried fruits.

If you don't eat many dairy products or calcium-enriched substitutes, then you may need a calcium supplement. We recommend you discuss this with your doctor or a dietitian.

The table below lists the approximate calcium content of some common foods.

| Food | Calcium content (mg) |

|---|---|

| 115 g (4 oz) whitebait (fried in flour) | 980 |

| 60 g (2 oz) sardines (including bones) | 260 |

| 0.2 litre (⅓ pint) semi-skimmed milk | 230 |

| 0.2 litre (⅓ pint) whole milk | 220 |

| 3 large slices brown or white bread | 215 |

| 125 g (4½ oz) low-fat yogurt | 205 |

| 30 g (1 oz) hard cheese | 190 |

| 0.2 litre (⅓ pint) calcium-enriched soya milk | 180 |

| 125 g (4½ oz) calcium-enriched soya yogurt | 150 |

| 115 g (4 oz) cottage cheese | 145 |

| 3 large slices wholemeal bread | 125 |

| 115 g (4 oz) baked beans | 60 |

| 115 g (4 oz) boiled cabbage | 40 |

Note: measures shown in ounces or pints are approximate conversions only.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D is needed for the body to absorb and process calcium and there's some evidence that arthritis progresses more quickly in people who don't have enough vitamin D.

Vitamin D is sometimes called the 'sunshine vitamin' because it's produced by the body when the skin is exposed to sunlight. A slight lack (deficiency) of vitamin D is quite common in the UK in winter.

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) has issued guidance on safe sunlight exposure which aims to balance the benefits of vitamin D against the risks of skin cancer from too much exposure to sunlight.

Vitamin D can also be obtained from some foods, especially from oily fish, or from supplements such as fish liver oil. However, it's important not to take too much fish liver oil.

Because we don't get enough sunshine all year round in the UK, and because it's difficult to guarantee getting enough vitamin D from what we eat, Public Health England recommends that everyone should take a 10 microgram supplement of vitamin D every day during the autumn and winter.

People in certain groups at risk of not having enough exposure to sunlight, or whose skin is not able to absorb enough vitamin D from the level of sunshine in the UK, are encouraged to take a daily supplement of 10 micrograms all year round.

For many people, calcium and vitamin D supplements are prescribed together with other osteoporosis treatments.

What else might help?

It's important to try to prevent falls. Simple things you can do at home include:

- mopping up spills straight away

- making sure walkways are free from clutter or trailing wires.

Some hospitals also offer falls prevention clinics or support groups – ask your doctor if there's one in your area.

Smoking can affect your hormones and so may increase your risk of osteoporosis. We strongly recommend you stop smoking. Support is available if you wish to stop.

Drinking a lot of alcohol can affect the production of new bone, so we recommend keeping within the maximum amounts (14 units per week) suggested by the government.

Related information

-

Exercising with arthritis

Find out more about exercising with arthritis and what types of exercises are beneficial for certain conditions.

-

Diet

There’s a lot of advice about diets and supplements that can help arthritis. We explain which foods are most likely to help and how to lose weight if you need to.

Diagnosis

There are no clear physical signs of osteoporosis and it may not cause any problems for some time. If your doctor thinks you may have osteoporosis, they may suggest you have a DEXA (dual energy x-ray absorptiometry) scan to measure the density of your bones.

The scan is readily available and involves lying on a couch, fully clothed, for about 15 minutes while your bones are x-rayed. The dose of x-rays is very small – about the same as spending a day out in the sun. The possible results are:

Normal – Your risk of a low-impact fracture is likely to be low.

Osteopenia – Your bone is becoming weaker but your risk of a low-impact fracture is relatively small. You may or may not need treatment depending on what other risk factors you have. You should discuss with your doctor how you can reduce your risk factors.

Osteoporosis – You have a greater risk of low-impact fractures and you may need treatment. You should discuss this with your doctor.

Who should have a scan?

There's no good evidence that screening everybody for osteoporosis would be helpful. However, you should talk to your doctor about having a scan if any of the following apply to you:

- you’ve already had a low-impact fracture

- you need steroid treatments for 3 months or more

- you had an early menopause (before the age of 45)

- either of your parents has had a hip fracture

- you have another condition which can affect the bones – for example, coeliac disease, inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis), rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes and hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid)

- you have a body mass index (BMI) of less than 19.

How to work out your body mass index:

- Multiply your height in metres by itself – e.g. 1.7 (m) x 1.7 = 2.89

- Divide your weight in kilograms (kg) by the number you got in stage 1 – e.g. 53 (kg) ÷ 2.89 = 18.3

- The result is your BMI e.g. 18.3

For most people a healthy BMI is between 19 and 25.

Your doctor may use an online scoring tool called FRAX®, developed by the World Health Organization (WHO), to help assess your risk of fracture and to help decide whether you should have a DEXA scan or treatment for osteoporosis.

Treatment

If you’re diagnosed with osteoporosis following a low-impact fracture, then the fracture will need to be treated first. The next step is to begin treatment to reduce your risk of further fractures.

Treatment of fractures

Most fractures are first treated in A&E, and you'll usually have a follow-up appointment at a fracture clinic to see how things are going.

Unless you have a vertebral compression fracture, you'll probably have a cast on the affected area to stop it moving and allow the fracture to heal. In some cases the fracture may need to be manipulated by a specialist before the cast is put on. This may be done in A&E or you may be admitted to hospital. You're also likely to be admitted to hospital if the fracture needs surgical fixing.

It's likely that you'll need pain relief medications, for example:

- painkillers (analgesics), such as paracetamol, codeine and occasionally morphine

- non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen or naproxen.

Prevention of fractures

Self-help measures such as diet and weight-bearing exercise can help to reduce your risk of fractures, but a number of specific treatments are also available.

You're likely to have a bone density scan before you start treatment, although this may not be needed, for example if you're 75 or over. Once you've started treatment your bone density may be monitored in one of the following ways:

- bone density scans, usually of the spine and/or hips, every 2–5 years depending on your individual circumstances.

- blood and urine tests to show how well your bone is renewing itself – these aren't so widely available as bone density scans.

If you're taking hormone replacement therapy (HRT), you'll also have regular blood pressure checks and breast scans (mammograms).

Your bone density should start to improve after 6–12 months, although you may need longer-term treatment to further reduce your fracture risk.

Bone renewal is a slow process so it's important to continue treatment as your doctor advises – even though you won't be able to feel whether it's working.

Because longer-term treatment can sometimes have side-effects your doctor may suggest a break from your treatment after 3–5 years. The benefits of osteoporosis treatment last a long time so these won't be lost if your doctor does suggest a 'treatment holiday'.

Your treatment will depend on your individual circumstances, and you should discuss this with your doctor. Types of treatment include:

- calcium and vitamin D

- bisphosphonates (alendronate, risedronate, ibandronate, etidronate, zoledronate)

- teriparatide and parathyroid hormone

- raloxifene

- calcitonin

- denosumab

- strontium ranelate

- hormone replacement therapy (HRT).

Strontium ranelate

This drug, which was produced under the brand name Protelos, was discontinued in 2017 but is now being produced again under the brand name Aristo. We will have further information on this drug soon.

If you were previously taking Protelos, you may want to speak to your doctor about Aristo.