Introduction

Clinical communication skills (of which history taking is one part) are among the most important skills for any healthcare practitioner to acquire – this can only be achieved through regular practice. A good history backed up by clinical examination findings will lead you to a diagnosis. Below we look more closely at the key questions that need to be addressed.

Are the symptoms from the joint or the soft tissues?

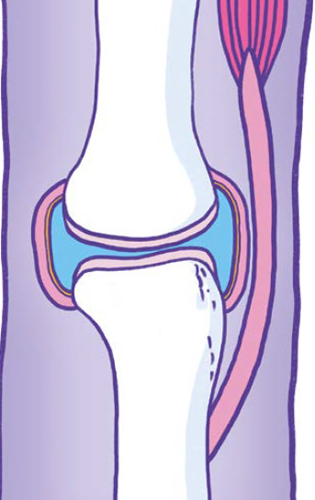

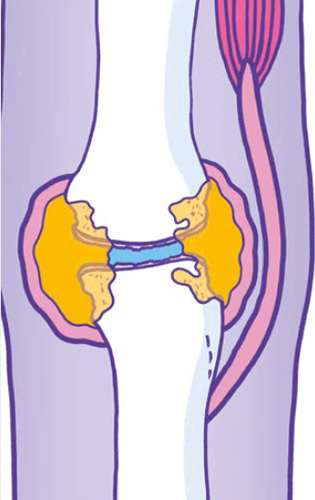

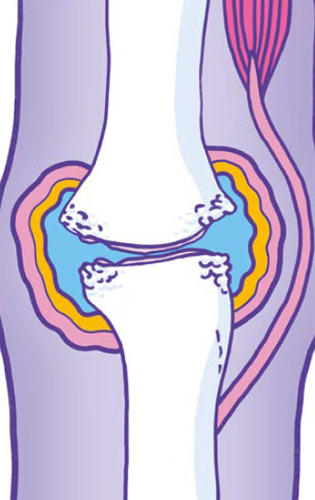

The structures that are shown below represent diagrammatically the changes that occur in the two main types of arthritis. However, it is important to identify those cases where pain may appear to arise from the joint but is in fact referred pain – for example, where the patient describes pain in the left shoulder, which might in fact be referred pain from the diaphragm, the neck, or perhaps ischaemic cardiac pain. In cases where examination reveals no abnormalities in the joint, other clues will be obtained by taking a thorough history. A common cause of widespread pain with normal joint examination for example is fibromyalgia.

X-ray and cross-sectional diagram of a synovial joint and it’s periarticular structures.

X-ray and diagrammatic representation of an index finger MCP joint affected by rheumatoid arthritis.

X-ray and diagrammatic representation of an index finger MCP joint affected by osteoarthritis.

Is the condition acute or chronic?

You will need to listen to the patient’s history to find out:

- When did the symptoms start and how have they evolved? Was the onset sudden or gradual?

- Was the onset associated with a particular event – for example, trauma or infection?

- Which treatments has the condition responded to?

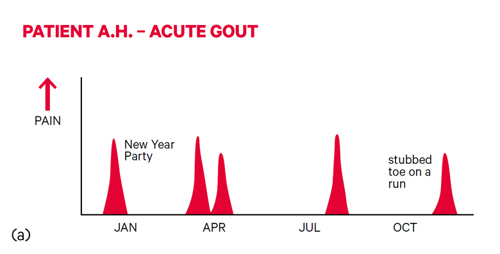

The way in which symptoms evolve and respond to treatment can be an important guide in making a diagnosis. Gout, for example, is characterised by acute attacks – these often start in the middle of the night, become excruciatingly painful within a few hours, and respond well to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

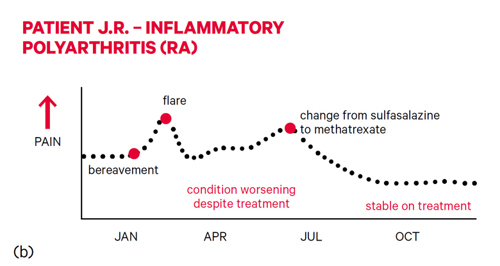

Musculoskeletal symptoms lasting more than six weeks are generally described as chronic. Chronic diseases may start insidiously and may have a variable course with remissions and exacerbations influenced by therapy and other factors. It may be helpful to represent the chronology of a condition graphically as shown below:

Is the condition inflammatory or non-inflammatory?

The main symptoms of musculoskeletal conditions are pain, stiffness and joint swelling.

Assessment of these symptoms and clinical assessment can allow differentiation to be made between inflammatory and non-inflammatory conditions. Inflammatory joint conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), are frequently associated with prolonged early morning stiffness that eases with activity – whilst non-inflammatory conditions, such as osteoarthritis (OA) are associated with pain more than stiffness, and the symptoms are usually exacerbated by activity.

Pain

As with all pain, it is important to record the site, character, radiation, and aggravating and relieving factors.

Patients may localise their pain accurately to the affected joint, or they may feel it radiating from the joint or even into an adjacent joint. In the shoulder, for example, pain from the acromioclavicular joint is usually felt in that joint, whereas pain from the glenohumeral joint or rotator cuff is usually felt in the upper arm. Pain from the knee may be felt in the knee but can sometimes be felt in the hip or the ankle. Pain due to irritation of a nerve will be felt in the distribution of the nerve – as in sciatica, for example. The pain may localise to a structure near rather than in the joint – for example, the pain from tennis elbow will usually be felt on the outside of the elbow joint.

The character of the pain is sometimes helpful. Is it sharp, deep, achy, burning or stabbing? Pain due to pressure on nerves often has a combination of numbness and tingling associated with it.

Pain of a non-inflammatory origin is more directly related to use – the more you do the worse it gets – and may be relieved by rest. Pain can be sharp and stabbing or achy at times.

Pain caused by inflammation is often present at rest as well as on use and tends to vary from day to day and from week to week in an unpredictable fashion. It flares up and then it settles down and can be associated with tenderness to the touch. Severe bone pain (suggestive of underlying malignancy) is often unremitting and persists through the night, disturbing the patient’s sleep.

Stiffness

In general, inflammatory arthritis is associated with prolonged morning stiffness which is generalised and may last for several hours. The duration of the morning stiffness is a rough guide to the activity of the inflammation.

Non-inflammatory arthritis, such as osteoarthritis of the knee, tends to cause localised stiffness which may be short-lasting (less than 30 minutes) but can recur after sitting for short periods.

With inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, where joint destruction occurs over a prolonged period, the inflammatory component may eventually become less active and give way to secondary mechanical pain as a result of the damage. It is therefore sometimes difficult for patients to distinguish between pain and stiffness, so your questions will need to be specific.

Joint swelling

A history of joint swelling, especially if it is intermittent, is normally a good indication of an inflammatory disease process. Patients often describe rings becoming tight or a sensation of walking on pebbles.

There are exceptions however. Nodal osteoarthritis, for example, causes bony, hard and non-tender swelling in the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) and distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints of the fingers. Swelling of the knee is also less suggestive of inflammatory disease as it can also occur with trauma and in OA. Ankle swelling is a common complaint, but this is more commonly due to oedema than to swelling of the joint.

What is the pattern of affected areas/joints?

The pattern of joint involvement is very helpful in defining the type of arthritis, as different patterns are associated with different diseases.

Common patterns of joint involvement include:

Monoarticular – only one joint affected (e.g. septic arthritis)

Pauciarticular (or oligoarticular) – only a few joints affected (e.g. psoriatic arthritis)

Polyarticular – many joints affected (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis)

Axial – the spine is predominantly affected (e.g. ankylosing spondylitis)

As well as the number of joints affected, it is useful to consider whether the large or small joints are involved, and whether the pattern is symmetrical or asymmetrical. Rheumatoid arthritis, for example, is a polyarthritis (it affects lots of joints) that tends to be symmetrical (if it affects one joint, it will affect the same joint on the other side), and if it affects one of a group of joints it will often affect them all, for example, the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints.

Note, however, that this describes established disease and early RA can affect any pattern of joints.

Spondyloarthritides, such as psoriatic arthritis, are more likely to be asymmetrical and may be associated with inflammatory symptoms, such as early morning stiffness involving the spine. Osteoarthritis tends to affect weight-bearing joints and the parts of the spine that move most (lumbar and cervical).

This table provides a summary of typical features of some common musculoskeletal conditions and what to look for.

What is the impact of the condition on the patient’s life?

Understanding the impact of the disease on the patient is crucial to negotiating a suitable management plan.

Ask open-ended questions about functional issues and difficulty with day-to-day activities. It may be easiest to get the patient to describe a typical day, from getting out of bed to washing, dressing, toileting etc. Potentially sensitive areas – such as hygiene or sexual activity, mood, depression and anxiety – should be approached with simple, direct, open questions. The impact of the disease on the patient’s employment will be crucial.

A patient’s needs and aspirations are an important part of the equation and will influence their ability to adapt to the condition. Questioning around the things a person would like to do, but is currently unable to, may pinpoint key issues. What are their ideas, concerns and expectations? Later negotiations with the patient on balancing the risks and benefits of an intervention will be greatly affected by the patient’s priorities.

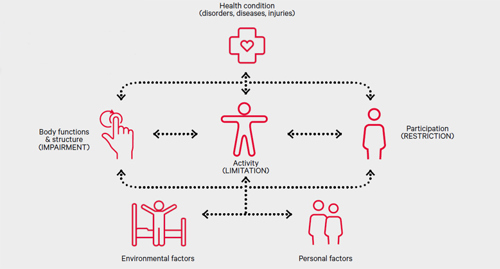

All healthcare practitioners should have an awareness of the relationship between functional loss, limitation of activity, and restriction of participation as indicated in the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (see model below). Being unable to fully flex a finger (loss of function) might lead to difficulty, for example, with fastening buttons (activity) which might have a minor impact on general life (participation). The same loss of function, however, might prevent a pianist from playing (activity) which, for a professional musician, might have a significant impact on his/her way of life (participation).

A model of disability - the relationship between loss of function, limitation of activity and restriction of participation. Based on the World Health Organisation International Classication of Functioning, Disability and Health. Disability and function are the result of the interactions between a health condition and contextual factors (environmental and personal factors).

Are other systems involved?

Inflammatory arthritis often involves other systems including the skin, eyes, lungs and kidneys. In addition, patients with inflammatory disease often suffer from general symptoms such as malaise, weight loss, mild fevers and night sweats. Osteoarthritis, in contrast, is limited to the musculoskeletal system and is not associated with immune activation. Systemic symptoms would therefore not be expected.

Fatigue and depression may be common in any arthritis where there is functional loss or chronic pain. A comprehensive history must include the usual screening questions for all systems as well as specific enquiries relating to known complications of specific musculoskeletal disorders.

Arthritis may occur on a background of other illnesses and it is important to consider other ongoing health issues, particularly with an increasingly ageing population. A combination of two problems will be worse than either one alone, and the impact on the patient will therefore be greater. In addition, other conditions may be affected by the treatments prescribed for the arthritis – for example, the presence of liver disease may limit the use of disease-modifying drugs for inflammatory arthritis, because most of these drugs can upset the liver.