pREMS assessment

- Be undertaken via a pREMS (paediatric Regional Examination of the Musculoskeletal System). This is similar to the adult REMS of each joint with a number of additional elements (special tests) that are explained below.

- The basic principles of the pREMS assessment are:

- Introduction

- Look

- Feel

- Move

- Function

- Special tests

Introduction

- Introduce yourself and obtain (verbal) consent/assent.

- Chaperone, as necessary.

- Observe child walking into clinic room or playing at rest.

- Appropriately expose (be aware of cultural sensitivity and gender).

- Watch for non-verbal signs of distress/pain (e.g. facial expression, withdrawing limb).

- Carefully check for symmetry and look for joint swelling, abnormal posture, muscle wasting.

- Perform the whole examination – joint involvement may not be obvious from the history and may have been overlooked by the parent or carer. Although changes may be subtle, joint involvement can be helpful to establish the diagnosis.

- A ‘copy me’ approach can be particularly helpful by sitting opposite the child – often makes the examination a form of play and helps with younger children.

- Further advice on general approach can be found on the PMM website.

Look

- Appropriately expose.

- Comparing both sides, look specifically for:

- rashes, muscle bulk, swelling, scars.

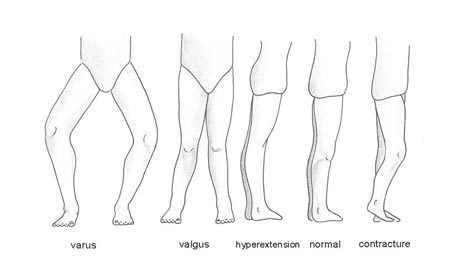

- posture and alignment of joints.

- footwear, walking aids or other bedside clues.

A useful overview of surface anatomy can be found on the PMM website.

Feel

- Temperature

- Swelling

- Tenderness

- Crepitus

- Muscle tone

Move

- Active movements (where patient moves joints): use ‘copy me’ approach.

- Passive movements (where examiner moves joints)

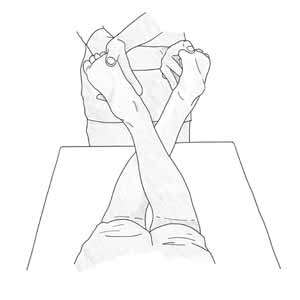

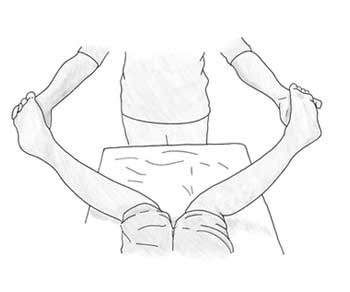

- Note ranges of movements – normal ranges can be found on the PMM website. A number of additional movements are shown below.

- Some children have hypermobile joints: further information on this can be accessed through the PMM website. Changes of hypermobility are symmetrical – if not, then consider pathology.

- If active movement is restricted but passive movement is normal this may indicate a muscular, tendon or nerve issue rather than an issue with the joint.

- Loss of movement can be recorded in degrees or as mild, moderate or severe.

Function

Can be assessed whilst watching patient from start of consultation:

Can be assessed whilst watching patient from start of consultation:

- How do they walk into clinic?

- How do they play with/use objects e.g. pencils, turning pages?

- How do they rise from chair/ground?

- How do they remove clothing items for examination?

Special tests

These can be performed depending on the joint involved and clinical scenario.

Measurement

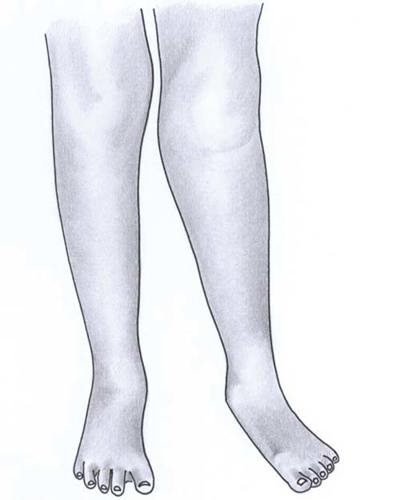

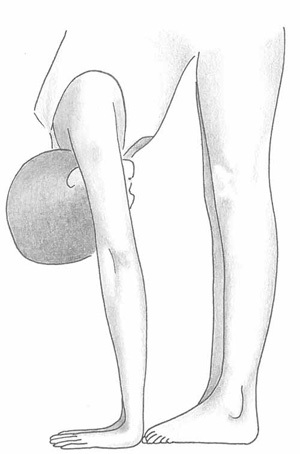

- Leg length: A discrepancy in the presence of MSK symptoms or limp should prompt referral to the appropriate specialist team. It should be noted that some children may have a leg-length discrepancy and are symptom free.

- Thigh girth: Again, a discrepancy in the presence of MSK symptoms can indicate an underlying related MSK disease and should also prompt referral. Examples include: quadriceps wasting due to underuse of affected limb or thigh swelling in the presence of knee arthritis on the same side.

Hypermobility assessment

- Useful where a hypermobility syndrome is suspected.

- Specifically comment on body habitus, skin elasticity, abnormal scarring, sclerae.

- Suspect Marfan’s syndrome if a positive family history is present: early death from aortic dissection or other clinical features such as high-arched palate, tall stature, ectopia lentis, spontaneous pneumothorax, varicose veins or recurrent hernias.

- Suspect Ehlers–Danlos syndrome if excessive bruising, elastic skin or unusual bruising is evident.

- Hypermobility can also be found in Down’s syndrome and osteogenesis imperfecta.

- Children with hypermobility can also develop inflammatory arthritis – this may be suspected with acquired loss of hypermobility/ asymmetrical changes.

- The Beighton score is used to assess hypermobility in adults; it is not validated or recommended for use in children.

- A hypermobility assessment can be found on the PMM website.

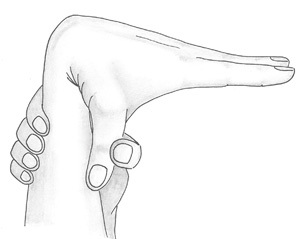

Nail fold capillaroscopy

- Specialist test, normally performed by the paediatric rheumatology team.

- Microscopy is used to examine the blood vessel wall structure under the nailbeds.

- Can be performed in: Raynaud’s phenomenon, juvenile systemic sclerosis, juvenile dermatomyositis, SLE and those with a suspected vasculitis.

Entheses assessment

- Patient has pain surrounding a tendon insertion site. Can be observed in subtypes of JIA (enthesitis-related arthritis).

- Observe for swelling, redness of affected area.

- Perform careful palpation and movement.

- Common sites of involvement include ankle (Achilles tendon insertion), knee (patellar tendon insertion), pelvis (adductor tendon insertion), elbow (flexor and extensor tendons). Often associated with sacroiliac joint tenderness.

- Can be further evaluated by USS/MRI of affected area.

- Further detail can be accessed on the PMM website.

Neurological assessment

- A detailed (peripheral) neurological examination may be necessary depending on the area affected.

- Tone/muscle power/reflexes/coordination sensation form basis.

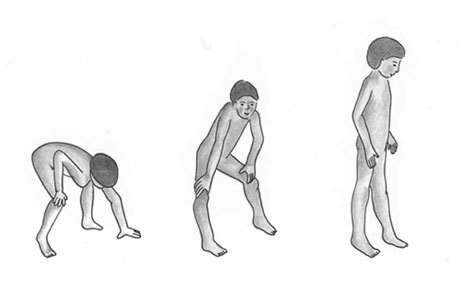

- Additional tests include:

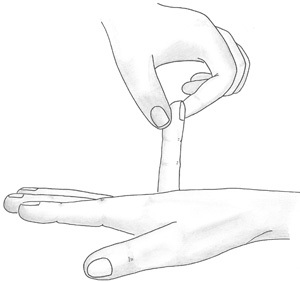

- Tinel’s test (median nerve irritation)

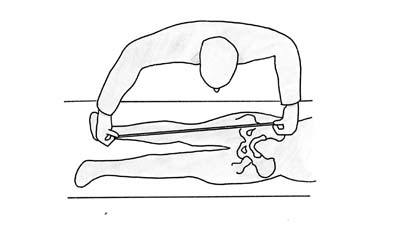

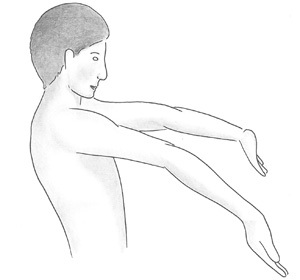

- Gowers’s test (proximal hip weakness).

Other assessments

- Peripheral pulse checks (where concerns with circulation).

- Clarke’s test of the knee to detect patellofemoral dysfunction/anterior knee pain.

- Cruciate and collateral ligament testing of the knee.

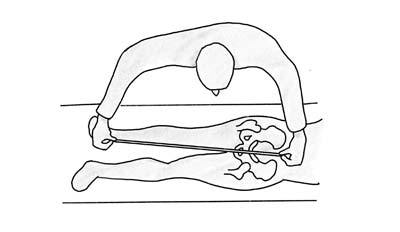

- Thomas test to detect a fixed flexion deformity of the hip.

- Trendelenburg test of the hip to detect gluteal muscle weakness.

- Schober’s test to detect a reduction in forward flexion of the spine.

- Straight-leg raise to test for L4, L5, S1 nerve root tension.

Pattern of joint involvement

Can help in differential diagnosis and defining type of arthritis. Patterns include:

- Monoarticular: one joint affected (e.g. septic arthritis).

- Oligoarticular (or pauciarticular): ≤4 joints (e.g. oligoarticular JIA).

- Polyarticular: ≥5 joints affected (e.g. polyarticular JIA, SLE).

- Axial: where the spine is predominantly affected (e.g. ankylosing spondylitis).