What is adult-onset Still’s disease?

Adult-onset Still’s disease, sometimes known as AOSD, is a rare type of inflammatory arthritis. As the name suggests, it can only be diagnosed in adults.

Its name comes from another condition, Still’s disease, which is also known as systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). Systemic JIA is only diagnosed in children. AOSD is generally thought to be the same condition as systemic JIA, but there are some differences between them.

Adult-onset Still’s disease is an autoimmune condition. This means that the condition is caused by your body’s immune system. The immune system protects us from infection and other threats to the body, but in AOSD it attacks your own body by mistake.

AOSD can cause pain and stiffness in your joints, as well as inflammation in other areas of your body.

Symptoms

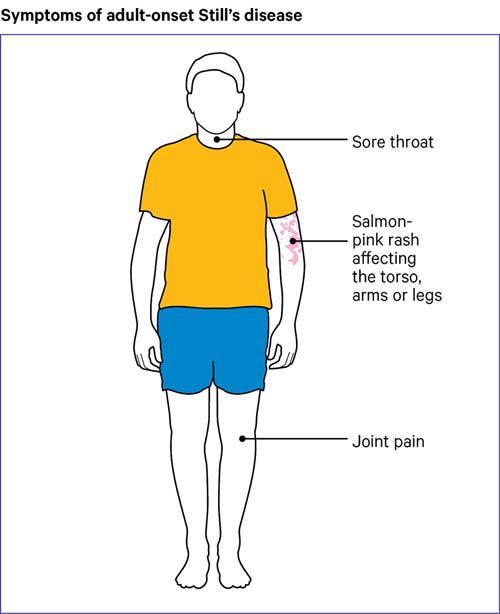

People who develop AOSD often have the following symptoms:

- a fever

- a sore throat

- arthritis or joint pain

- a salmon-pink rash that comes and goes quickly.

Some people may not have all these symptoms at once, which can make it difficult to diagnose the condition.

The fever caused by AOSD usually goes up and down a few times during the day, usually going up in the afternoon or evening. But some people may have a fever all the time or have spikes in the fever in the mornings.

People can also have pain in their muscles or joints, or unexpected weight loss before the fevers start. AOSD can also cause fatigue, which is an overwhelming feeling of tiredness that doesn’t always get better with sleep or rest.

People with AOSD frequently experience joint pain, going on to develop arthritis. Arthritis causes pain, swelling and stiffness in the joints. AOSD most commonly affects the knees, wrists and ankles, but it can also affect the hands, feet, hips, elbows, shoulders and jaw.

Sometimes people have a sore throat caused by swollen lymph nodes in their neck. The lymph nodes are part of the immune system. You have them all over your body and they help your body defend itself from infection.

The rash that occurs with AOSD is salmon-pink in colour, and normally appears on the torso, arms or legs. It can also appear on the palms of your hands, the soles of your feet or your face.

The symptoms of AOSD can start suddenly or gradually. When symptoms start suddenly, this is known as a flare. This often happens for no particular reason.

Flares can vary in how badly they affect people with AOSD, and they can be very frequent or may be years apart.

Some people with AOSD only experience the symptoms for a short period, but for others the condition can return or continue causing symptoms for a long time.

Information Related to Symptoms

How will it affect me?

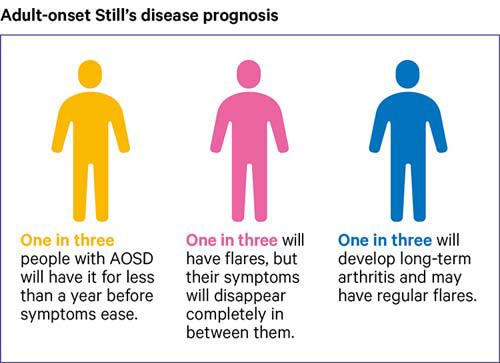

It’s hard to predict how AOSD will affect you, but generally the condition tends to affect people in one of three ways.

Around one-third of people diagnosed with the condition will have it for less than a year before their symptoms ease. They might need to stay on drug treatment for a bit longer to make sure the condition is completely under control.

Another third of people will have flares of the condition before symptoms disappear completely. The flares can sometimes be years apart, and they don’t always affect the joints. Symptoms may get easier to manage in later flares.

Around one-third of people with AOSD will go on to develop long-term arthritis and may have flares quite regularly and for a long time. In some people, AOSD can eventually cause permanent damage to the joints, usually if people have inflammation in their joints for a long time. The risk of this is reduced if the condition is brought under control by drugs.

Many people with AOSD can live a full and normal life with the right treatment.

Some of the symptoms of AOSD might make you feel more conscious of how you look. People with AOSD often comment on changes to their weight, as well as the look of their joints. Some people also experience increased sweating due to the fevers.

Talk to your doctor if you’re becoming aware of any of these changes, as they may be able to offer you some support and advice.

Complications

Other rarer, complications of AOSD include:

- enlargement of the spleen or liver

- problems with how well your liver works

- pericarditis, which causes inflammation of the layer of tissue around the heart

- pleural effusion, which is a build-up of fluid in and around the lungs

- scarring of the lung, known as interstitial lung disease, which could lead to breathing issues

- other lung problems.

Rarely, AOSD can cause a condition known as macrophage activation syndrome (MAS), which can affect the liver and blood cells.

Some of these complications can be life threatening if they’re not treated, so it’s important that if you develop any of the following problems, you contact your doctor as soon as possible:

- a cough

- difficulty breathing

- chest pain

- any other new symptoms, such as losing weight or feeling unwell.

Causes

The cause of AOSD isn’t known, but we do know it generally affects more women than men, and that it mostly starts in people aged between 16 and 35. But adults can get it at any age.

It’s thought that people who develop AOSD may have genes that make them more likely to get it, but that there also needs to be something in the environment that triggers the condition, such as an infection.

Diagnosis

It can sometimes be difficult to diagnose AOSD, because some of the symptoms – such as the fevers, sore throat and rash – can be confused with other problems, like infections, other autoimmune conditions or some types of cancer known as lymphoma.

It’s also a very rare condition, so some GPs may not have seen people with it before. It’s important you mention all your symptoms when you see a doctor, as this can help them rule other things out.

There’s no single test for AOSD, so your diagnosis will be based on:

- a history of your symptoms

- a physical examination

- blood tests

- ruling out other conditions and infections.

Blood tests will usually show a high level of inflammation in people with AOSD – this is shown in two tests known as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP). Other blood tests to look at the number of cells in your blood and how well your liver is working, can also help diagnose it.

You might need to have scans, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or x-rays as part of your diagnosis, but these aren’t always helpful in diagnosing AOSD as the condition may not have any visible signs.

Treatments

Once you have been diagnosed, you will be seen at a rheumatology clinic in a hospital. You’ll usually see a specialist doctor, known as a rheumatologist, and a rheumatology nurse specialist.

Your rheumatology team will be able to advise you on treatments and things you can do for yourself to reduce the symptoms of AOSD.

You may need to have regular blood tests to check the number of different types of cells in your blood, and to see how well your liver is working.

Drugs

The main drugs used to treat AOSD are:

- non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs)

- steroids

- biological therapies.

You should carry on taking the drugs given to you by your doctor, even in periods when you’re feeling better, as this will reduce the risk of flares. If you’re considering stopping your treatment, you should discuss this with your doctor.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

NSAIDs will be the first treatment for people who have a mild form of AOSD. They’re effective at reducing the symptoms of fever and arthritis, but most people will need to take NSAIDs alongside other drugs to bring the condition fully under control.

NSAIDs include aspirin, ibuprofen and naproxen. Some can be bought from supermarkets or chemists, but others are only available on prescription. They’re available as tablets, creams and gels, injections and patches.

Like all medicines, NSAIDs can cause side effects, particularly if they’re taken in high doses or for a long time. Your doctor might also prescribe you a drug called a proton pump inhibitor to protect your stomach while you take them, as they can irritate the lining of the stomach.

Steroids

Steroids will often be given as one of the first treatments for people with AOSD, particularly if the symptoms are severe, as they help to reduce symptoms quickly in many people with the condition. Steroids will normally be given as tablets or liquids that you swallow. A commonly used steroid for AOSD is prednisolone.

Steroids can also be given in higher doses usually over a few days, known as pulses, for more serious symptoms of AOSD that affect organs such as the liver and heart.

Most people with AOSD will need treatment with steroids, as they’re a very effective treatment for inflammation, joint pain, fever and symptoms affecting the organs. Your doctor will try to give you steroids for as short a time as possible, as they can cause side effects, such as weight gain and the bone condition osteoporosis, if taken for a long time.

Steroids can also be given as injections for arthritis – either directly into an affected joint or into a muscle to help reduce inflammation across the body.

Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs)

DMARDs can be used to reduce the effects of the immune system attacking your own body. They’re long-term medications, which means it often takes weeks or months for them to work. You will usually need to keep taking them even if they don’t seem to be working at first, and you’ll need to continue them when you start to feel better.

If steroids and NSAIDs aren’t helping to bring your condition under control or aren’t suitable for you, you might be put onto a DMARD to see if this can help. You might need to carry on taking steroids and NSAIDs as well to reduce your symptoms.

A commonly used DMARD for AOSD is methotrexate, and this is helpful for a lot of people with the condition. But it may not work for everyone. If methotrexate doesn’t work for you, your doctor may want to try other DMARDs, such as:

You may be given another treatment known as intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) if you have other complications of AOSD.

Biological therapies

Biological therapies are newer drugs to treat inflammatory types of arthritis, such as AOSD. They block certain chemicals or cells in your immune system to reduce the activity of your condition.

They can be used as a treatment for AOSD if treatments like steroids and DMARDs haven’t worked.

Like DMARDs, they can take a long time to start working – so it’s important you keep taking your biologic medication even if you feel better or if it doesn’t seem to be working at first.

Anakinra is a biological therapy that blocks a protein produced by your immune system known as interleukin-1 (IL-1). It can be used to treat AOSD and may also be used if you develop macrophage activation syndrome (MAS).

Tocilizumab is another biological therapy that can be used to treat AOSD if other treatments haven’t worked. It targets a different chemical known as interleukin-6 (IL-6).

You can’t take anakinra and tocilizumab together, but you might be swapped from one to the other if one doesn’t work for you.

There are other biological therapies that target other parts of the immune system. If the above treatments don’t work, your rheumatologist might suggest you try another biological therapy.

You may need to take a biological therapy alongside another DMARD, usually methotrexate, to fully bring the condition under control.

Physical therapies

Your doctor may refer you to a physiotherapist for advice on exercise and physical activity. You can also refer yourself to one in your local area, but you might need to pay for this.

Physiotherapy might be helpful for advice on exercise tailored to you. A physiotherapist might provide you with a specific exercise plan. They can also provide exercises in a warm-water pool, known as hydrotherapy or aquatic therapy.

The Chartered Society of Physiotherapy provides a service to help you find a physiotherapist near you.

Occupational therapy is useful for getting advice on managing daily tasks that your condition might make more difficult. For example, they can give you tips and gadgets to help with:

- personal care

- cooking

- dressing

- cleaning.

They will also be able to give you advice on ways you can pace your activities to manage fatigue and help you keep your independence.

Managing your symptoms

Exercise

Keeping as active as you can is important for your joints. There are many benefits to exercise. If you have arthritis, it can help you by maintaining the range of movement in your joints and strengthening the muscles that support them.

Though you might feel like resting when you’re in pain, exercising won’t make your arthritis worse. Try to start off doing small amounts of exercise and gradually increase the amount you do. Exercise, along with a healthy diet, can help you keep to a healthy weight which will reduce strain on the joints in your legs.

Exercise is also good for improving our mood and reducing fatigue. Though you may not feel like you have the energy to exercise, doing a small amount can make a big difference.

Diet

Research hasn’t shown any link between what you eat and AOSD. But being overweight can put extra strain on your joints, so it’s a good idea to keep to a healthy weight. This can also help improve your energy levels, as carrying extra weight can make you feel tired.

Eating a balanced diet of regular meals can help improve feelings of tiredness, which could help to improve the fatigue the condition causes, and will also help improve your general health.

Reducing the strain

Fatigue is common in people who have AOSD, and pain can sometimes get in the way of things you need to do.

Learning how to pace yourself and protect your joints can help manage your fatigue and reduce your symptoms. An occupational therapist will be able to give you advice on this, but there are also things you can do for yourself, such as:

- Try not overdo it on days when you’re feeling better.

- Think about how you do certain activities – is there an easier way you could do this instead?

- Change your position regularly and stretch.

- Plan things you need to do in advance and try to spread tasks out over a few days, rather than doing everything in one go.

- Take regular breaks and rest before you get tired.

- Try to spread the load of things you need to lift or carry over as many joints as possible.

Improving mood and sleep problems

If you are stressed or feel down because of your condition and how it is affecting you, this may also make your symptoms feel worse. Try things to reduce the effect on your emotional wellbeing, such as practising relaxation techniques or exercise. Drinking less alcohol and keeping a healthy diet can also help.

If your feelings are getting in the way of your normal life, it’s important you speak to a doctor, who will be able to give you other suggestions and refer you to specialists who can help. Talking therapies, such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) or counselling, can help reduce these feelings too.

Visit the NHS website to find out about the 5 steps to mental wellbeing.

Feeling low can often make you feel tired or struggle to sleep. Following the tips above can help reduce fatigue and tiredness, but you could also try the following:

- Go to bed and wake up at regular times.

- Download an app to help monitor your sleep.

- Do some relaxing exercise, such as yoga, to relax your muscles.

- Write a to do list for the next day, to help clear your mind.

- Have a warm bath or shower to get your body to the right temperature for rest.

If these techniques don’t help you, you should speak to your doctor, as they may be able to give you more advice or refer you to a sleep specialist for help.

Complementary treatments

There isn’t much research into complementary treatments for people with AOSD. If you want to try complementary medicines or therapies, you should discuss this with your doctor first, in case any treatments could interact with the medication they’ve given you.

It’s important you go to a therapist who is registered, or one who has a set ethical code and is fully insured.

Information related to managing symptoms

-

Eating well with arthritis

There’s a lot of advice about diets and supplements that can help arthritis. We explain which foods are most likely to help and how to keep to a healthy weight.

-

Exercising with arthritis

Find out more about exercising with arthritis and what types of exercises are beneficial for certain conditions.

-

Sleep

Disturbed sleep can affect your health and make the symptoms of arthritis worse. Find out how arthritis can affect sleep and how to improve your sleep pattern.

Living with adult-onset Still’s disease

Sex and relationships

If you’re feeling unwell or fatigued, or have joint pain, sex might be the last thing on your mind. But there are things you can do to maintain intimacy and relationships, and to have an enjoyable sex life.

Try to plan intimacy around times of the day when you generally feel better. Have a warm bath or shower before, to ease your joints. Talking openly with your partner about how you feel can also help, and your doctor should also be able to give you advice.

Fertility, pregnancy and breastfeeding

In a very small number of women, AOSD starts during pregnancy, and some women with the condition have flare-ups during pregnancy. Having AOSD can increase the risk of some problems with pregnancy, such as the condition worsening, problems with the baby’s growth or going into labour early.

It’s important to discuss pregnancy with your rheumatology team, as they’ll be able to give you advice on treatments and lowering the risk of any complications. They may also be able to refer you to other specialists for advice and support once the baby is born.

There are certain drugs, such as methotrexate, that need to be stopped before or during pregnancy. If you want to start trying for a baby, talk to your rheumatology team first before making any changes to your medication.

It’s thought to be safe to take steroids while pregnant and breastfeeding to keep the condition under control. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) may be used to treat flares that happen during pregnancy, and some DMARDs are safe to use.

Sometimes NSAIDs can cause a slightly increased risk of miscarriage if taken in the early stages of pregnancy, so it might be an idea to avoid these while trying to get pregnant. You might also need to stop taking them a few weeks before your due date, as they could cause problems with the baby, but your doctor will be able to give you advice on this.

It’s usually fine for men with AOSD to carry on taking their medications when trying for a baby.

Work

You might find working difficult with AOSD, but there are things in place that can support you in your working life.

Anyone working with a disability in the UK has a right to equal treatment at work. The Equality Act 2010 protects you from discrimination. This also means that your employer should work with you to make the workplace accessible to you by making ‘reasonable adjustments’.

Reasonable adjustments can be anything from adjusting your working hours or providing you with special equipment that helps you do your job.

If your employer can’t make all the adjustments you need, you may be able to get help through Access to Work. This can cover grants to pay for equipment or adaptations, support workers to help you, or help to get to and from work.

Access to Work operates in England, Scotland and Wales. There is a different scheme in Northern Ireland.

Research and new developments

Research has shown that there are certain cells and chemicals in the immune system that may be behind the inflammation in adult-onset Still’s disease.

While there are treatments that target some of these chemical signals – namely anakinra for IL-1 and tocilizumab for IL-6 – there are other chemical signals or cells that could have an even bigger link to the condition. It’s thought that treatments currently in development that target these may be more effective for people with AOSD.

Claire’s story

It was 29 September 2018. I woke up and I just knew I wasn’t well. I felt completely exhausted and unable to lift my body. I’d had a temperature and it would vary – sometimes it would be at a low level the whole day and then get worse at night. It always seemed to happen at around 6.30 pm.

I spent a couple of weeks going to the doctor almost every day. I went into hospital for a couple of days after one bad evening where I couldn’t control my temperature. My tummy looked like I was pregnant.

The second time, I was in hospital for eight days. They were doing lots of tests. I could hardly get out of bed to walk. By the sixth day, they came and diagnosed me.

They gave me a tiny little white pill – a steroid tablet. And I thought they were joking; I couldn’t believe that was the answer. I was shaking with happiness thinking that I was going to be sorted. Unfortunately, it’s not been like that, but I was fortunate enough to be diagnosed.

I was off work for seven months and over that time doctors tried me with different medicines. But they haven’t really worked very well, and I found the side effects too overwhelming.

At the moment, I’m not on anything other than herbal medicine. I am also having Bowen therapy, which is a complementary treatment where a therapist uses their fingers gently to stimulate nerve pathways in the body.

I’ve been married for 25 years and leading up to my diagnosis, the worst thing was family, friends and my husband asking me why I wasn’t wearing my wedding rings. My fingers were so swollen, they didn’t fit me.

It was tough for my sons. I went to a meeting at my son’s college and I didn’t take the lift because I thought I was going to embarrass him, so I walked up the stairs. Then I sat there feeling tired, thinking how I was going to be able to have a conversation.

I used to do lots of travelling with work, and I was very fortunate that when I returned to work, they slotted me into a similar role that doesn’t need the same amount of travelling. Your wrists and fingers ache more after a good day’s typing, and your voice and throat get sore, especially after talking on the phone a lot.

I go to Pilates. At first, I got my instructor to come around to the house to do some really basic moves, and it was just impossible for me to even do breathing without feeling dizzy. Now I’ll try and do the moves and I’m amazed that I can do most of it again.

It’s been a difficult time, but my family, friends and faith, attending my local church, have helped me through.

It’s always on your mind – am I going to go up the stairs, or will I need to save my energy for a meeting and use the lift? Do I need to use my blue badge to help reserve my energy when I go shopping?

I can start walking and everything gets loosened up and I think I’m fine, but as soon as I stop and rest, I start to get a bit more frozen and achy and painful. It’s always there.